Diary Entry #3

Today, I Hit My Quota

Throughout the last few entries, we’ve covered the basics of authentication coercion and relay attacks, as well as some novel real-world edge cases exploited by our team that use these techniques. This time let’s start digging into what comes after the first successful relay attack on a client’s network.

At the very start of a penetration test, the PKFOD ethical hacking team does not have any credentials at all. We are usually provided a network connection on the user network and that’s about it. Within our penetration testing methodology, we refer to this as the pre-authentication phase. During this phase, we are getting our bearings, learning where the key systems are and gathering as much information as possible. This information will allow us to move to the next phase of the methodology, gain authentication and this is where the real hacking begins.

In this phase, we use the information we’ve previously gathered to exploit weaknesses that might allow us to recover a set of credentials. Any set will do and we aren’t very concerned with privileges at this point in the test. If we identified the presence of multicast name resolution protocols, or IPv6, we have a solid chance at abusing features of these protocols to obtain our first NetNTLM password hash. As we’ve mentioned before, there are two things we can do and we always try both. First, we could try to “crack” that hash and obtain access to associated plaintext password. Secondly, we could relay that hash to other services on the network. Both are dependent on factors that we don’t control, so we hedge our bet and relay credentials as we attempt to crack them.

The most valuable information we can collect on an internal network is behind a pay wall. We (generally) need credentials to access Active Directory. But if we can get access, we can obtain a list of all users, all security groups, all group members, GPO information, permissions and so on and so forth. This means our first relay target is often the LDAP service on a domain controller, because any account, no matter its privileges, can at least authenticate to Active Directory and read Active Directory data.

LDAP: The First Relay

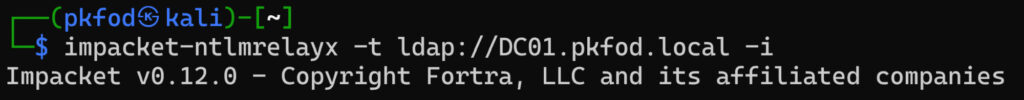

So, as one does, we spin up some basic tools like Responder or MITM6 and begin poisoning specific network traffic to obtain user credentials. If we are lucky, we will get at least one set of user credentials and if we are even luckier, we will be able to relay them to either LDAP or LDAPS. If successful, this means that LDAP signing or LDAPS channel binding is disabled.

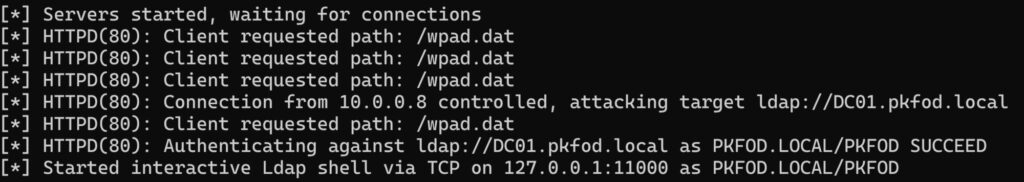

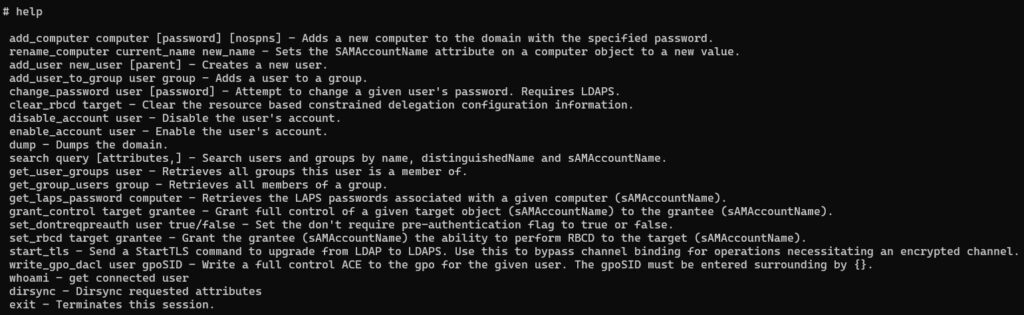

Now that we have successfully authenticated to LDAP, what should we do? Well, if we pop open the LDAP console, a simple “dump” command will extract valuable information we can use later in the test.

But sadly, assuming we’ve relayed a standard low-privileged user account, there isn’t much else we can do, as most of these other highly-valuable commands require elevated privileges.

Besides other methods of gathering information, it looks like we can only change our own relayed user account’s password, which could be valuable, if we can’t crack their password. But then again, we are already authenticated to LDAP as that user and PKFOD generally doesn’t change user passwords during ethical hacking engagements since it can be quite disruptive. Is that really all we can do?

Abuse the Quota

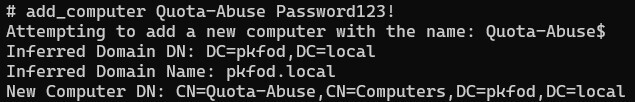

By default and therefore in most cases, there is one other permission that is provided to everyone in Active Directory – the ability to add computer accounts. This is essentially equivalent to joining a system to the domain and is apparently not considered a privileged action by Microsoft (or most organizations). But let’s think this through. The ability to add user accounts is highly restricted, but anyone can add computer accounts? In previous Pentest Diary entries, we’ve already demonstrated just how valuable a single computer account can be for techniques like authentication coercion. So, let’s create one.

And just like that, we have a genuine foothold in the environment. We now have a computer account (QuotaAbuse$) with a known password. We don’t have to rely on password guessing, password cracking, or user account relays for initial access anymore, we can authenticate directly! Let’s look into why this attack actually works.

The Machine Account Quota is set, by default, at as a domain-level parameter within the ms-DS-MachineAccountQuota property. This value sets the maximum number of computer accounts that can be created by any authenticated object on the domain.

This quota corresponds to the permission “Add workstations to domain”, which by default is provided to the “Authenticated Users” group.

Herein lies the issue, as by default any authenticated object in Active Directory can create up to 10 computer accounts. As shown, this can be abused to turn limited access to LDAP via a NetNTLM password hash relay into a full-blown backdoor account to be used for further abuse. By executing this attack, we’ve moved past the gain authentication phase of our penetration testing methodology and into the post authentication phase, where we begin examining the soft underbelly of your network using our backdoor account.

What to Do Next

Organizations should treat domain-join actions (i.e., computer account creation) as a privileged action and restrict these permissions accordingly:

- Set the Machine Account Quota to zero to prevent low-privileged users from creating computer accounts.

- Delegate the ability to join systems to the domain to a subset of privileged accounts by appropriately setting the create computer object permission.

- Monitor Active Directory for the attempted creation of unauthorized computer accounts.

Do these attack vectors exist in the environment you are testing or defending, right now?